Unlike other religious leaders, Benedict wrote only one rule of life, not one for men, one for women, and another for lay people. He wrote one rule that can be lived by men and women inside and outside the monastery as monks, nuns, and lay people.

Benedict’s Rule is eminently flexible, allowing each monastery to find its own charism. In “MONASTICS IN THE WORLD” Father Laurence recalls his friend and teacher, Dom John Main O.S.B., who placed the tradition of Christian Meditation at the center of the monastic life of the contemplative community he founded. Before his death in 1982, John Main spent his years as a mature Benedictine monk teaching the practice of meditation to all.

John Main’s conviction was that Saint Paul’s direction to “pray always” was not meant just for specialists — Cistercians, Benedictines, or Carthusians– but for all believers. Out of that conviction sprang what he called a “Community of Love”. Today, there are meditation groups and meditation centers around the world following his teaching. Many of these meditators have become Oblate members of the Community.

This guide presents Father Laurence’s thoughts on: the Oblate tradition, discerning a calling to Benedictine Oblation, the process for becoming an Oblate, and the hallmarks of the commitment an Oblate makes to his/her community.

The Tradition of the Benedictine Oblate Today

“The Oblate community is an exploration, made in the vision of the Benedictine Tradition, of an integrated, spiritual form of life appropriate for men and women today.”

1. THE TRADITION OF MONASTICISM

Monasticism is one of the oldest human institutions. It testifies to the unquenchable thirst of the human soul to awaken to its origin. The first Christian monks appeared early in the Church’s history as an attempt to recover the primary experience of faith. They began as hermits in the Near East, flowered in the Egyptian desert in the fourth century AD and then spread to Europe. The Desert Tradition was brought to the west by John Cassian and it strongly influenced both Celtic and Benedictine forms of monasticism. Early Christian monasticism had a strongly lay character and developed in contrast to the clerical state. Monks were free spirits seeking God through Christ, alone or in community. By the 6th century St Benedict, who was not a priest, inherited a diverse set of Christian monastic forms. In his famous Rule for Monasteries he simplified and synthesized this tradition and produced a vision of life that has inspired Christians of all walks of life down to the present day.

2. THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT

Benedict began his monastic life as a young man as a hermit. Later he became the spiritual father of a number of monasteries for which he wrote a short Rule, which he described as a “little rule for beginners”. It is about 9000 words and is mostly concerned with the practical details of community life. But the way it deals with these details allows it to transcend its time and culture. His essential question for entry into the community is “does the monk truly seek God?” The vows of stability, obedience and conversion of life are supplemented by disciplines of mindfulness and self-harmony aimed to bring the monk to the experience of the love of God. Prayer is central to the daily life and provides the framework in which the other two essential elements; work and Lectio Divina (sacred reading) are integrated. The spirit of the Rule is one of moderation, tolerance, respect, discipline and the liberty of love, it is not a theological treatise – he recommends Cassian and earlier monastic teachers for that. But Benedict testifies to a truly incarnate and daily spiritual life, which has a universal and timeless relevance.

3. OBLATES

Originally oblates (from the Latin “oblatus” – offered) referred to children placed in the monastery by their parents, They would choose whether to remain as monks once they reached the age of reason. Later, as the monastic institution became more formalized under church law, oblates were resident members of the community who for various reasons did not take officially binding vows. In time, the term oblates also covered people who lived outside the monastery but who had a special relationship with it.

4. JOHN MAIN

John Main founded a new kind of Benedictine community based on the Rule and on the practice of meditation as taught in the Desert Tradition. From its beginning he gave equal value to the forms of commitment made by monks or oblates. Oblates in his vision were not merely “attached” to a monastic family; they were fully participatory and contributing members. This represented both a return to an ancient tradition and an important new development.

Today the community formed around the world through meditation testifies to John Main’s belief that the “contemplative experience creates community”. Meditation takes us to the essence of the monastic identity: the single-minded search for God. Then it naturally awakens our sense of sharing this search with others.

Of course not all meditators become oblates. The World Community for Christian Meditation represents, along with diverse other inspired groups, today, a contemporary form of Christian contemplative life. John Main believed that meditation offered a path for all people into the deepest faith-mystery of Christian experience. His great contribution was “the way of the mantra”; a simple discipline that could be practiced daily by people in any walk of life. For some meditators the monastic roots of this tradition offers them in a particular personal way a context and vision for their pilgrimage.

5. WHY PEOPLE BECOME OBLATES

Practicing meditation every day does not mean one has to become an oblate. Why then do some meditators do so? Because they feel the value of expressing in a visible, human way the sense of community they feel with others seeking God on this path. Because we all need support, encouragement, inspiration and the challenge of others to deepen our commitment. Because the sense of tradition needs to be made real in a living community and the Benedictine tradition is deep and wide enough to give hospitality to a very broad spectrum of people.

Also because they see that modern life can lack meaning, spiritual focus, and balance. In the Benedictine vision as developed for 1500 years they see the elements of a healthy style of life: a balance and harmony of body mind and spirit. A context for the study of scripture and spiritual thought which the way of meditation naturally encourages and makes a source of delight.

The oblate vision integrates the twin forms of monastic life, solitude and community. Basic to this vision is the centrality of prayer – the different forms of prayer, which lead us into the “pure prayer” of simplicity and oneness as taught by the Desert Tradition. It offers a liberating sense of spiritual discipline appropriate to one’s temperament and state of life.

6. THE COMMITMENT

Being an oblate is not a legalistic undertaking. The Rule of St Benedict itself is a highly flexible document that demands to be interpreted and has received very diverse interpretations throughout its history. In the same way the life of an oblate is not bound to a set of rules and regulations. The Rule is a yardstick, a way of seeing the straight in the crooked. It is not in the Benedictine spirit of valuing the root virtue of ‘discretion’ to have a book of rigid rules.

The three basic vows of the Benedictine Rule are principles of life to which the oblate makes a commitment of heart and mind:

STABILITY: This does not mean merely physical stability but an inner fidelity to the community one has joined. But this stability is given meaning by the commitment to the deeper stability of one’s inner being, calmness and peace of mind, an ever-growing rootedness in the Spirit.

OBEDIENCE: All groups require a structure of obedience however informal. Benedict emphasizes the importance of mutual obedience and consultation. But the essential obedience here is that of the spiritual ear attuned to the Word of God, which resonates in all peoples and all situations, and a quick responsiveness to this Word.

CONVERSION: Dramatic experiences of conversion may have their value but their meaning is in opening a new phase of life. This vow is a commitment to be always a pilgrim, living an ongoing conversion of one’s way of life by an ever-fuller harmony with the principles of peace, tolerance, selflessness and generosity and the courage to say the truth about injustice.

These general principles are lived out in personal ways. There are, however some particular elements of the oblate commitment which also highlight its meaning:

- A commitment to the twice daily practice of meditation each day in the tradition which John Main handed on.

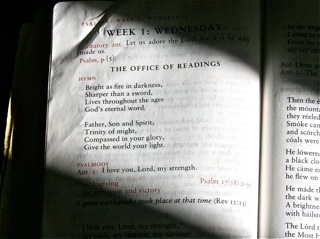

- Some form/part of the Divine Office as morning and evening prayer.

- A short reading of the Rule of St Benedict each day.

- Frequent reading of Scripture, Lectio Divina.

- Sharing in the work of the community to pass on the Christian tradition of Meditation.

7. COMMUNITY

There are many different forms of monastic life and community. Today’s “Monastic” – another possible term for “Oblate” – may live singly, in marriage or in one of several forms of shared life with others. All these ways of life are livable in the Oblate Community. We recognize today both the need for a pluralism of forms and for a spirit of adventurous experimentation as this ancient tradition evolves.

The basic element of the Oblate Community, however, is the “cell”. This word has a long monastic tradition referring originally to the monk’s cave or room. With us it is used to describe presence, not only physical space. Therefore an oblate cell can exist where there is even one oblate living alone with rare contact with other oblates. It also refers, more usually, to a group of oblates living close to each other. This cell will agree and arrange to meet with regularity, to meditate, to share the Word and to consider their ways of sharing in the work of the wider community.

There is also a newsletter and occasions like retreats, the John Main seminar and other events in the meditating community at which oblates can meet and share the strength of their common bond.

8. ENTERING THE COMMUNITY

As the Rule describes, entering a community is a process and requires discernment. This is not because the community is any kind of elite. But because the full benefit of entering demands the clearest possible understanding of one’s reasons and of the call to which one is responding.

The first step is to make contact with an oblate or cell and make an expression of interest. Then a period of Postulancy can begin for which there is the simplest of ceremonies. During this period, of about six months, the postulant would benefit from attending the meetings of the cell and other events in which meditators meet. (The meetings of the cells are never “closed”). One can also use this period to develop a clear understanding of what the oblate community is about and what it is not. A reading of John Main’s “Community of Love” would be helpful at this stage, along with an initial reading of The Rule of St Benedict.

Secondly, the Oblate Novitiate begins, where possible, with a short ceremony of welcoming and prayer for the fruitfulness of this step. The oblate novitiate lasts a year and may be extended. During this time the oblate novice begins a study of the Rule, the Benedictine tradition and the teaching of John Main and other teachers of the Christian contemplative tradition. Although this formative year is not primarily about reading, it is important to set aside time for this work. The real formation is in the deepening of awareness that takes place as one continues to meditate day by day with a quiet sense of the community of meditators near and far.

The third stage is the Final Oblation which is made at the expressive moment in one’s spiritual journey as a step into a community and the living tradition it embodies. It is not a step that should be rushed and there should be a period of discernment, such as a retreat, during which one can reflect upon the meaning of the Benedictine “vows” as they apply in one’s own particular circumstances.

9. THE FORM OF OBLATION

Oblation is made both to and within community. The context of oblation is to The Community of Christian Meditators, a monastery without walls : The World Community for Christian Meditation.

SUMMARY

Meditation is about the journey to the Center – one’s own Center and the Center, which is God. Christian Meditation is the spiritual journey into this center by becoming centered in the heart and mind of Christ by a way of silence, simplicity and stillness.

Becoming an oblate in this community is an assent and a commitment to the recentering of one’s life and of one’s awareness in this mystery of Christ and of God. It is one way, among others, in which this universal human journey is given meaning and focus and is enriched, no less for the good of others as for our own, by joy and peace.

Laurence Freeman, OSB

Email: Laurence@wccm.org